Bois de la Brigade de Marine

'This melancholy spot with its tangle of wildwood . . . will for all time be a Mecca for pilgrims from beyond the western ocean.’

—MG James G. Harbord, USA

23 June 1923

Although the United States' entry into the war on April 6, 1917 gave the Allies considerable cause for hope, that hope was tempered by the apparent military weakness of the U.S. Army. On December 31, 1917, almost nine months after the Americans' entry into the war, there were only 174,884 American troops in Europe. A few months later, in March 1918, the Germans launched a new offensive and achieved considerable success against the British, penetrating their lines more than 35 miles. Sensing the Allies' desperation, General Pershing, commander-in-chief of the American Expeditionary Force, offered American troops to the Allies wherever they were needed. With American help, the Germans were stopped in Picardy and Flanders.

The Germans had even more success against the French two months later. After capturing Soissons, the German Army advanced down the Marne River valley toward Paris. Demoralized French troops were falling back. Once again, American troops were rushed to the front.

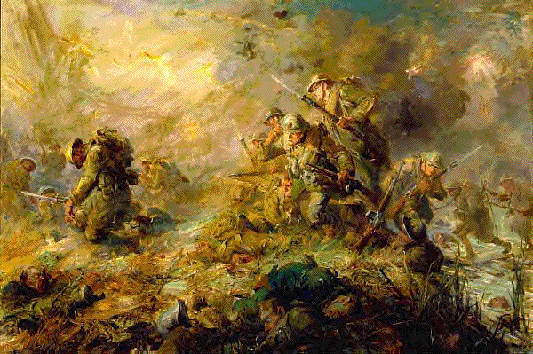

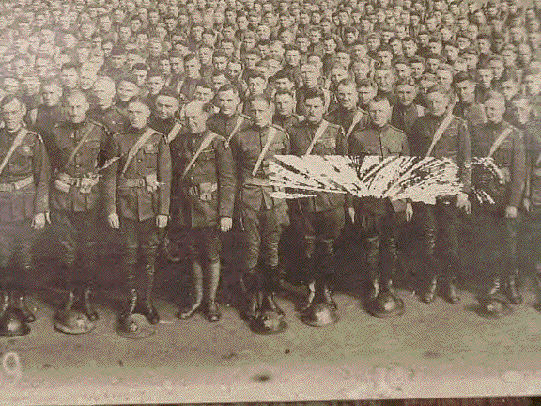

One of the American units thrown into the breach was the 5th Marine Regiment. The 5th Marines were part of the 2nd Division, which had recently rotated out of the trenches and was heading toward a training area northwest of Paris when the Germans struck. With the German Army driving toward Paris, the Marine Brigade was ordered to take up a position near Lucy-Le-Bocage along the Paris-Metz Highway on June 1. Over the next five days, the Marines repulsed a series of German attacks. On June 6, they counterattacked. Their objective was Belleau Wood, an area of rough terrain, heavy woods, and sharply rising knolls. The Marines' effort was further complicated by inaccurate French maps of the area and faulty intelligence. Although the Marines were told the woods were lightly defended, they were held by a regiment of crack German troops. Working with rifles and bayonets, the Marines dug the well-concealed Germans out of their defensive positions. By the end of the day, the Marines had taken two-thirds of the woods. For the next couple of days, the Marines consolidated their positions and fought off a series of counterattacks.

On June 11, as the regiment began another assault on the woods, Lieutenant Petty's dressing station was hit by German artillery fire and gas shells. Although his gas mask was damaged when he was knocked to the ground by an exploding gas shell, Petty continued to provide aid to the wounded Marines in the aid station until he had to evacuate the position. At that point, he assisted a wounded officer through the artillery barrage to a position of relative safety.

Despite strong German resistance, the regiment captured the last portion of the woods under German control on June 23, 1918. For its part in the battle of Belleau Wood, the 5th Marine Regiment gained the grudging respect of the Germans, who named them "Devil-dogs." The French Army went even further, renaming the woods "Bois de la Brigade de Marine."

Address of Major General James G. Harbord, U.S. Army

Dedication of ‘Belleau Wood’

July 22nd. 1923

It is very appropriate that this shell-torn wood and blood-soaked soil should, with the consent of our great sister republic, pass forever to American ownership. It is too precious in its associations, too hallowed with the haunting memories of that fateful June of five years ago to be permanently sheltered under any flag, no matter how much beloved, other than our own, and now in the quiet sunshine of a happier summer it has become a tiny American island, surrounded by lovely France. I cannot conceive that in all time to come our country will every permit the pollution of this consecrated ground by the foot of an invader marching on that Paris, which Americans here died to defend.

Insignificant in area, out of the ordinary track of travel not especially picturesque, and with no particular traditions in peace or war, this ancient hunting reserve of the Chateau of Belleau, came into the spot-light of history by being at the spear-head of the German thrust for Paris in the last week of May 1918. For a short period, the music of its sonorous name was heard in all Allied lands, and for its brief day it held the head lines throughout the world. The great crises of history pass unheeded by the actors in the drama, and it is not until after the event that the historian can say that particular hour on a crowded day was heavily charged with fate. The accident of place, the chance stroke of a zero-hour wrote the name of the Bois de Belleau on the tablets, and with it chronicled the immortal fame of the Marine Brigade, and their comrades of the Second Engineers.

There were no better troops than our Marines in any Army, and it is fitting that for this Memorial to the American arms, there should be chosen this battlefield where they fought with such desparate valor, to redeem which so many of them gave their lives. The Marine brigade was placed in line on the afternoon of June 1st. Its front extended from Thiolet Farm on the Paris-Metz highway through Lucy-le-Bocage, and over Hill 142, to beyond Marigny and Champillon. It roughly followed the southern edge of this valley and faced towards Bouresches, Belleau and Torcy. For several days there was nearly continous fighting as the enemy tried in vain to gain ground toward Paris. On the 6th of June, the Marines made the first attack on the Germans in this wood and in the village of Bouresches. Sibley’s battalion captured the southern end of the wood, and took the little town.

The fighting was practically continuous until June 25th when the last German was driven out and Major Shearer reported, “This wood now exclusively U.S. Marine Corps.” A few days later, the French Army Commander, General Degoutte, officially renamed the wood to be known forever on all French maps as the Bois de la Brigade de Marine. There were killed in and around this wood 670 officers and men of the Marine Brigade, and 7,321 were wounded. The slain were in the proportion of about one to every five wounded, while the usual battle ratio is one killed to every seven or eight wounded. This means that many wounded Marines remained in the fight until killed by a second or third wound.

I may perhaps be forgiven if this ceremony today brings to me more clearly than to some of you, the half blurred vision of that other summer. In fancy I can still see the splendid columns in forest-green deploying across the fields from the great highway between Paris and Metz, in memory I endure once more the suspense of these days and nights, and am torn again by the consciousness of the cost at which this wood was taken. Who better than I should know that the men who poured out the red wine of life on these slopes, were the very flower of our race, the straightest of limb, the keenest of vision and the most dauntless of spirit.

This melancholy spot with its tangle of wildwood, its giant boulders, its mangled trees, with here and there the wreckage of war, a helmet, a rusty canteen or, perhaps in some lonely forest aisle the still tangible evidence of deadly hand-to-hand struggle, will for all time be a Mecca for pilgrims from beyond the western ocean. Mothers will consecrate this ground with their tears; fathers with grief tempered with pride will tell its story to their younger generation. Now and then, a veteran for the brief span in which we shall still survive, will come here to live again the brave days of that distant June. Here will be raised the alters of patriotism; here will be renewed the vows of sacrifice and consecration to country. Hither will come our countrymen in hours of depression, and even of failure, and take new courage from this shrine of great deeds.